When Venomous Snake Bites Serve the Common Good (Little Green Notebook)

But not the marital vows

My brother Robert and I got into plenty of fights growing up, as is the nature of siblings. Robert’s sudden death by drowning in 1999 put an end to our squabbles and planted a marker in my mind of The Last Fight Robert and I Ever Had.

Robert possessed my father’s love of snakes coupled with an erratic and impulsive personality, a questionable combination. His python, for example, escaped and lived free in the house for months, thanks to his carelessness. We finally found her in one of Robert’s Dingo Boots, sticking her head out like a telescope.

When Robert was free of the shackles of parents, he free-handled venomous snakes in Australia. In an article he wrote for Reptile Hobbyist, published in August 1998, he confessed his fantasy of handling “forbidden snakes and lizards.” Though siblings through and through, I do not share this fantasy.

One day I was visiting Robert at his house on Cecil Lane.

“I need you to help me clean a snake cage,” he said. Robert was wheelchair bound, the result of his erratic and impulsive personality, with limited use of his arms and hands.

I went inside, ready to assist.

As he was unlocking the large wooden and glass box, I realized just which snake cage he was talking about. Inside, a Gaboon viper coiled and hissed. This gorgeous creature raised his enormous, triangular head, which housed two-inch long fangs, the longest of any snake. Though they rarely strike humans, these African slitherers are one of the world’s fastest-striking snakes.

“I’ll hold him down with this,” Robert said, gesturing to a forked metal prong in his lap, “and you just reach in and get the newspaper.”

There was no way on God’s green earth I was sticking my hand into that Gaboon viper’s cage. We argued. We raised our voices. We ranted and swore. “Maybe you don’t have anything to live for, but I have children and a husband!” I said, storming out the door.

This morning, I found an article that reminded me of The Last Fight Robert and I Ever Had. It described a man who has subjected himself to venomous snake bites, lots of them. “Over nearly 18 years, … Tim Friede, 57, injected himself with more than 650 carefully calibrated, escalating doses of venom to build his immunity to 16 deadly snake species. He also allowed the snakes … to sink their sharp fangs into him about 200 times,” The New York Times reported on May 2, 2025.

From a simple garter snake bite in childhood to intentional bites from cobras and black mambas, Friede’s body is now a wellhouse of antivenom. I cannot attest to his intentions, but the outcome serves the common good.

According to the article, the combination of deforestation, human sprawl, and climate change have led to an increase in venomous snake bites worldwide, but the research and production of antivenom has not kept pace.

Where does antivenom even come from? I’d always assumed that antivenom came from a lab in a faraway kingdom run by Merlin the Magician, who waved his wand over bubbling vials of serum, transforming their contents into a life-saving elixir.

In reality, it comes from antibodies created by injecting small amounts of various venoms into “donor animals,” specifically horses and goats.

Well of course. I learned how vaccinations work in fifth grade and have only increased my understanding since. Antivenom works like an immediate vaccination.

Like all antibodies, antivenoms are specific. There are different antivenoms for box jellyfish, black widow spiders, black mambas, and other potentially lethal biters. This specificity is just one challenge for hospitals to have the right antivenom on the ready.

We’re experiencing a worldwide shortage of antivenom. Its production technique is largely unchanged from when it was first invented in 1895, it’s expensive, it has a limited shelf life, and there is a woeful lack of funding into antivenom research.

The current antivenom for our American pit vipers is CroFab, which uses serum from sheep in Australia who have been envenomated by four different pit vipers. CroFab is a “monoclonal antibody,” a word that became politically polarized during the height of the COVID pandemic.

Back to our snake-bitten friend, Mr. Friede.

One Dr. Jacob Glanville, CEO of a company searching for a solution to the specificity issue of antivenom, had almost given up when he heard about Mr. Friede. Testing revealed that antibodies in Mr. Friede’s blood provide full protection against thirteen snake species, and partial protection against six. This is a breakthrough.

Our country is in a crisis of magical thinking when it comes to science, and vaccines specifically. Still, I guarantee you that even the most anti-vax, monoclonal-antibody-fearing parent would not turn away the lifesaving antivenom CroFab if their own child were bitten by an Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake.

As for raising your own pit-vipers, beware. My brother’s wife left him when he brought that Gaboon viper home, and our hero-to-medical science, Mr. Friede, is also now divorced.

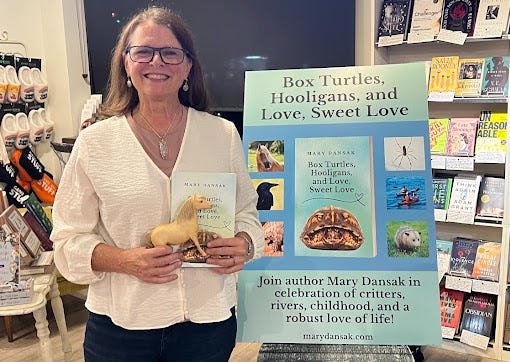

Box Turtles, Hooligans, and Love Sweet Love, a collection of my columns, is available on Amazon in paperback and eBook version. See my website, marydansak.com, to order from me directly. Join the hooligans!

Although I give venomous snakes the widest of berths possible, it is interesting to read how anti-venom is produced. We've had to use it on horses and dogs on our ranch in the past. Thankfully not people, though several neighbors got to experience the rattlesnake bite and anti venom journey. Hopefully the shortage of anti-venom can be resolved🤞.

A truly fascinating read! I had no idea about how snake anti-venom was created, and the story about your brother, the free-roaming python, and the viper... yikes.